Click to enlarge photographs

Biography

Declan O’Neill

I am a retired professional photographer living in the South Island, New Zealand. My journey into photography began in Ireland in my mid-teens when I first picked up my father’s Voigtlander Prominent camera and pointed it at anything that took my fancy. I didn't really know what I wanted to say with my camera but was entranced by the magic of making images. My parents were visibly alarmed when I announced that I wanted to be a photographer and promptly enrolled me for a degree in French language and literature just in case I had any ideas about actually following through with my reckless ambition. Like so many graduates with a semi-useless degree, I became a teacher and it took a quarter of a century to escape that particular black hole. I wandered into management training for which I was spectacularly ill-suited. Not surprisingly, I had a mid-life crisis and instead of doing something sensible like buying and restoring a Mark 2 Jaguar decided to throw in my steady but boring job and embrace a career in the one thing that I was really passionate about, photography.

For 20 years or so I ran my own photographic and video production company. It’s not a career that, in general, supports a lavish lifestyle. Nor is it quite as creative as some would have you believe. I photographed everything from irrationally upset babies to temperamental thoroughbred yearlings worth millions of dollars. I never got those jobs you read about where you get flown to an exotic location to photograph famous models cavorting on a sun drenched beach. I did, however, photograph a range of tapware. Not everyone realises how difficult managing reflections on polished steel can be so it had its own rewards, I guess.

When the pickings were slim on the photography front I could rely on corporate clients to tide me over by commissioning videos that made their floor polishing machines look interesting and dramatic. I never realised what true creativity is until I was asked to produce a video about milk tankers.

I’m now retired and divide my time between enjoying my family, photographing the scenery of New Zealand and trying to finish a garden which after a decade is still incomplete. While I am moderately happy with my landscape photography, it is frustrating that the most extreme response it gets from viewers is that it is ‘nice’ or ‘beautiful’. ‘Nice’ as far as I am concerned is somewhat of an insult when it is used as an adjective to describe a photograph.

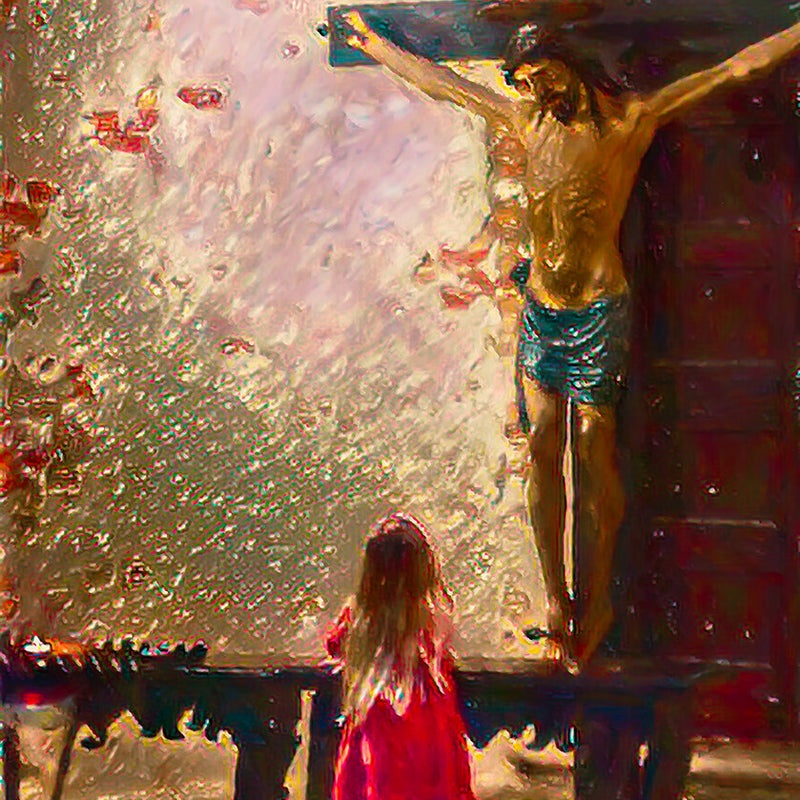

I’ve taken more than enough pretty photographs and in my seventh decade wanted to chew on something a little more substantial. There comes a point when you tire of the carefully curated perfection of landscape. I wanted to capture a world that isn’t perfect or even beautiful. I began searching for what the French philosopher Roland Barthes called the ‘punctus’ which he defines as 'the sensory, intensely subjective effect of a photograph on the viewer'. I find it somewhat ironic that my seemingly useless French degree provided the key to unlock my voice half a century later. This collection of photographs is part of my quest to find a voice that is authentic and not the result of a desire to please an audience. I want my images to ask questions of the viewer and above all I don’t want anyone to call them ‘nice’.

Commentary

It took me a very long time to work out why the work of Ansel Adams leaves me indifferent. It isn’t so much the laboriously crafted perfection of the images because you have to admire the work of a man who spent hundreds of hours in a darkroom burning and dodging until he had adjusted the landscape to his ideal of how he wanted it to look. I am indifferent because the images make me think of rocks: so often his subject matter. Rocks are just rocks. Similarly, the landscapes of Ansell Adams are just landscapes. I use the word ‘just’ to underline the fact that, for me anyway, the images raise no questions. They ask nothing of me. When I look at my own landscape work I realise that my images are also just a mirror held up to nature rather than a lamp to illuminate it, to use the brilliant metaphor used by M. H. Abrams in his critical examination of 18th and 19th century English literature. Abrams saw 18th century writing as a reflection of outward reality whereas 19th century artists wrote to illuminate their inner and outer world. My landscapes were nothing more than the result of the mechanical clicks of a shutter. I had no role to play. I was a mirror.

Ansel Adams: Cathedral Rock

It was not until I discovered the later works of Rembrandt that I began to understand how an artist can challenge the viewer to ask questions, sometimes uncomfortable ones. Rembrandt began his career by executing exquisitely crafted canvases. The works are brilliant but his mastery was in the service of others. Rembrandt’s old age was problematic as fashions changed and commissions dried up. At this time he started on a final series of searing self-portraits. You can’t look at these canvases and not feel a compelling curiosity about what prompted him to portray himself with such uncompromising honesty. He challenges us to ask questions about mortality, self-image and honesty.

Rembrandt’s technique is totally different in these last works. The brushwork is rough and the paint is applied with none of the delicate finesse of his youth. Not surprisingly, his critics were quick to assume that advancing years had blunted his huge talent and that these last portraits were the sad swan song of a once brilliant artist.

Rembrandt, Self Portrait With Two Circles

The most enigmatic of these later paintings is entitled 'Self Portrait with Two Circles'. There has been much debate about the significance of the two circles drawn behind the artist. Did they represent hemispheres of a map of the world? But why no geographical references? Or are they, as Simon Schama suggests in his book 'Rembrandt’s Eyes’, a sort of middle finger rebuke to his critics showing that he had not lost his drawing skills? Was he saying, 'I know what the rules are but they no longer serve my purpose?'.

Bacon, Self Portrait

The other artist who has provided inspiration for this collection of photographs is Francis Bacon. His self-portraits are, to my eyes, a direct descendant of Rembrandt’s work. He wrote of Rembrandt, 'The mystery of fact is conveyed by an image being made out of non-rational marks'. Bacon took Rembrandt’s psychological depth and melded it into his brilliant abstract technique. While Bacon’s technique polarises viewers, it is impossible to ignore the driving, almost painful, emotional intensity of the canvases.

Edward Hopper, Automat

A third inspiration has been the gaunt works of Edward Hopper. He has an unnerving ability to make his human subjects seems awkward and out of place in their surroundings. His colours are always just slightly too rich and add to the general air of disquiet. He has taken isolation and almost romanticised it.

Hammerschoi, Interior with Piano and Woman In Black

Finally, I was inspired by the works of Vilhelm Hammerschoi whose domestic interiors feature women as almost accidental objects yet they carry the weight of the viewer’s interest. To underline their ambiguous presence, the women invariably have their backs to the painter. The monochromatic tones add to the sense of heaviness and, maybe, foreboding. Like Hopper, there is a feeling that the human does not fit comfortably into the painting but it’s not always easy to decide why this is so.

These artists gave me the courage to work outside the boundaries I had observed for so long. I was fascinated by Bacon’s reference to ‘non-rational marks’ and have embraced this idea in my treatment of the camera image; I was intrigued by the strange tension between person and place in Hopper and Hammerschoi; and Rembrandt’s embrace of a radical new technical approach in his old age encouraged me to experiment and break conventions of composition and treatment.

In the end, I felt compelled to follow my instincts, especially after a diagnosis of Stage 4 cancer, which gave me a sense of liberation and freedom. Illness makes us look at the world in a different way and notice things previously unremarked. Most importantly, it allowed me to find the voice for which I had been searching my entire life.